Let’s Talk About Persisting

The Subtle Art of Stick-to-Itiveness

We’ve spent considerable time together thinking about the Portrait of a Graduate and the relationship between the skills we hope our children develop by graduation and how we support them in developing those skills along the way, what we often refer to as the act of becoming.

And we know what some of you might be thinking.

“Okay, enough already.”

“We already do this.”

“We don’t need one more thing.”

We see you. We hear you. We’ve been there too.

That feeling that we already do so much is real. The prevailing axiom in schools is that we do not have enough time, money, or training. And that is a tough place to sit, especially right now.

But this is also an important moment to pause and ask a different question.

If we already do many of these things, how might we do them more intentionally?

How might we evolve our practices so that modeling and guided practice of intellectual behaviors are visible, shared, and accessible to all learners?

So let’s look at one habit, not as one more thing, but as a lens.

Let’s look at Persisting.

What Persisting Really Involves

Persisting involves staying with a problem, especially when it becomes challenging, and adjusting your approach when what you are doing is not working.

At its core, persisting means that a learner can:

Analyze a problem

Develop and use a system or strategy for approaching it

Identify the steps to be taken

Know what information needs to be gathered

Collect evidence about whether the strategy is working

Recognize when a strategy needs to be abandoned or revised

Keep working toward a solution

This kind of persistence relies on thinking. And critically at that.

Consider this. No matter how many times we tell ourselves we will try harder to go to the gym, many of us still have memberships we rarely use. The issue is analysis. Why is this not working? What needs to change? What system would actually support the goal?

That distinction matters a lot.

How Do We Teach Persistence?

Let’s try it out.

How do we teach the practice of persistence?

Can you list the ways?

We expect the lists to vary by grade and content area.

But we all agree that persistence is such a powerful behavior.

So, what if we taught persistence using an explicit mental model, rather than assuming students would pick it up along the way?

Step 1: Make Persistence Visible

First, it helps students develop a deeper understanding of what this Habit is.

Remind students that Persistence is a set of teachable behaviors for approaching problems, challenges, and goals, academic and non-academic alike.

Persistence means being able to:

Analyze a problem

Use a system or strategy

Identify steps

Gather necessary information

Monitor progress

Revise strategies when needed

Keep moving toward a solution

Step 2: Introduce the Persistence Triangle

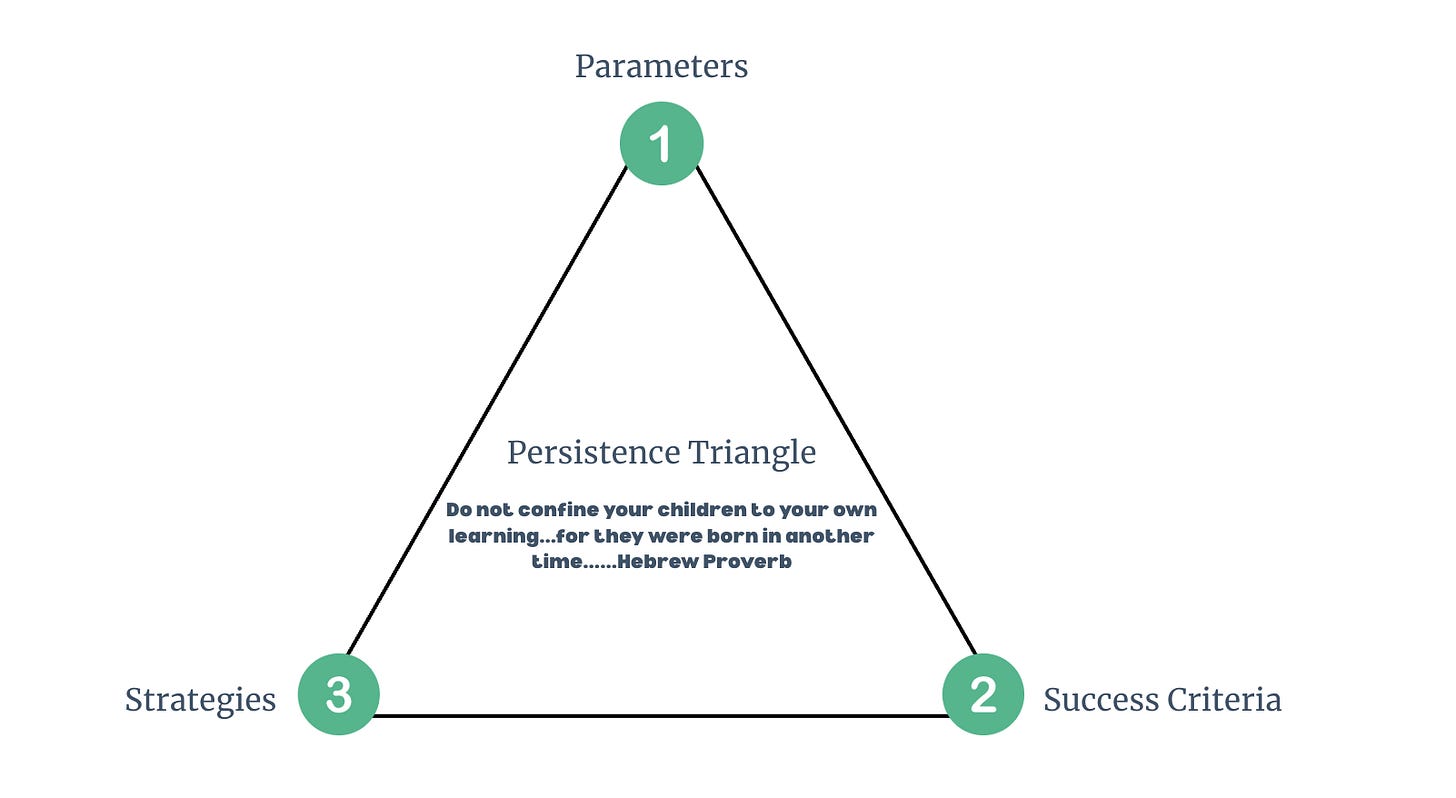

To help students internalize this Habit of Mind, many teachers have found success using the Persistence Triangle.

This model helps learners:

Define and analyze a problem

Generate possible strategies

Clarify what success looks like

It provides a concrete structure for problem-solving.

Each corner of the triangle represents a set of questions students should consider before beginning work.

The Three Corners of the Persistence Triangle

Parameters / Resources

What information do I have?

What information do I need?

What materials are available?

How much time do I have?

Who can I work with?

Possible Strategies

Brainstorm

Draw on past experience

Use strategies from similar problems

Learn from other sources

Criteria for Success

What does success look like?

How will I know I am finished?

When will I know it is time to switch strategies?

What feelings or evidence will tell me that?

We often find that strong learners move back and forth between the first two corners before focusing on the third. This is not a rule, but it can help students who tend to jump into the first strategy that comes to mind manage impulsivity and think more deliberately.

Let’s Test It

So if we gave you a quiz right now, would you pass it?

Could you explain:

What persistence is?

What the Persistence Triangle is?

Why it matters?

Yes. You could.

But now comes the more important question.

If I give you a problem to solve, how would you actually approach it?

You have one minute to solve this problem. Time yourself (this is serious!)

Nina is shorter than Oscar.

Priya is taller than Lena.

Nina is shorter than Lena.

Ethan is taller than Priya.

Ethan is shorter than Oscar.

Maya is taller than Oscar.

Question: Is Oscar taller than Nina?

After a minute, Stop.

How many of you immediately started drawing stick figures, lines, or names at different heights?

Most of us begin with the first strategy that comes to mind. That is normal and even natural.

Now, ask yourself: what is the problem I am trying to solve?

We bet many of you would not be able to answer this question.

Now retry the problem, and this time apply the Persistence Triangle by asking yourself:

What is the actual problem I am trying to solve?

What are the parameters?

What strategies could I use?

How will I know when I am done?

What did you just learn?

Persistence is more than a poster on the wall or the language we use with the community. It is about teaching students the behaviors associated with persistence and providing ample opportunities to practice them using protocols and mental models.

And this is where the learning is.

Good Habits of Mind are learned. We must be explicitly taught and practice deliberate thinking to become skilled at it.

And here is the key insight. Students must forget to use the triangle many times on the way to learning to remember it. Forgetting is part of the learning process.

Why This Matters Across Disciplines

The Persistence Triangle applies to nearly everything we ask students to do.

In writing, parameters include purpose, audience, topic, and format. Criteria for success might be a rubric or an authentic writing goal. Strategies include drafting a letter, a poem, a speech, or an argument.

In science, parameters include prior knowledge and available data. Strategies involve experimentation or research. Success may look like a coherent theory that explains the evidence.

Once students begin to internalize this model, they become more deliberate problem solvers. Teachers also become more intentional designers of learning experiences.

Teachers begin asking:

What information will students need?

How will they access it?

How much time and what resources are appropriate?

Who defines success, the teacher or the students?

How will students uncover or revise strategies?

Over time, students become more autonomous, and teachers become more conscious of their role in fostering persistence.

So, Where Does This Leave Us?

How do we lean into teaching the Habit of Mind of Persistence?

How do we help students apply these behaviors to everyday tasks, not just academic ones?

And if this is what emerges from a close examination of just one Habit of Mind, imagine what is possible when we are intentional about others, such as metacognition, flexibility, perspective-taking, and communicating with precision.

So the question remains.

Do we already do this?

Or is there more to be done?

-Nicole & Trici